|

TECHNOLOGY & SOCIETY ARTICLES

|

Manifest Technology Blog

-- Site:

| Articles

| Galleries

| Resources

| DVI Tech

| About

| Site Map

|

Articles:

| PC Video

| Web Media

| DVD & CD

| Portable Media

| Digital Imaging

| Wireless Media

| Home Media

| Tech & Society

|

Technology & Society:

| Technology & Society Articles

| PC Technology References

|

Simulation-Based Authoring for Serious Games

(SoVoz Inc., 6/2005)

by Douglas Dixon

Emergency Response Team Training

Game Development

Directing a Simulation

Growing SoVoz

Where's the Business?

References

"Serious Games"? Isn't that an oxymoron? In the video game

and training communities, however, serious gaming is an important emerging field

-- leveraging the tremendously engaging visuals and interactivity of 3D video

games to apply them to "serious" purposes other than entertainment.

And serious games are getting a lot of attention these days -- as demonstrated

by the two-day Serious Games Summit event held in spring 2005 at the

annual Game Developers Conference in San Francisco (www.seriousgamessummit.com).

This is the target market for soVoz, Inc., a Princeton, N.J. company

that is developing simulation-based learning systems (www.sovoz.com).

Stephen Lane, president, was at the Game Developers Conference demonstrating his

ProScena Studio software product, designed to allow even non-programmers

to rapidly create simulation-based 3D content for training, education and, yes,

gaming applications.

But can video games be serious? There's no question of the power of video

games for today's younger generations, and interactive 3D games would seem to

offer a natural training platform (certainly at least for scenarios like army

firefights). This developing interest in serious games comes from those

"people who realize that game-based learning approaches and simulation can

really make a difference in terms of how people learn," Lane says,

"especially given the fact that there's a whole generation of people who in

effect have been raised on games. They play games for leisure, but games haven't

really been used too much in a corporate setting, or in a training and education

context."

"This will make a big difference," he says. "You will have the

ability to experiment, and learn from experience, without all the risks that are

associated with doing it in the real world."

The government and military have a huge need for effective and timely

training. "The government offers some 60,000 courses a year," says

Lane, "and they wanted to move a lot of that online." The initial work

"was geared toward more traditional forms of distributed learning -- things

like web pages, PowerPoint presentations -- but they had not really thought in

terms of how simulation would play into it."

As part of this government effort, the Advanced Distributed Learning (ADL)

Initiative, sponsored by the Office of the Secretary of Defense, has

developed standards for courseware vendors (www.adlnet.org).

"The idea is to promote reusability of the content," says Lane,

"so when you create a new course, you could draw from a repository of

objects and assemble them together. And you can make content interoperable on

learning management systems that serve up the content."

To demonstrate the potential of its approach, soVoz has been working with the

ADL to develop a series of prototype applications, re-creating existing

simulations to see if they can be done faster and more effectively.

SoVoz has just completed a prototype Civil Support Team (CST) simulation for

emergency response teams. The inspiration for this project, says Lane, was that

"another company had developed this trainer a year before, but it took them

about six months to do it, and it really wasn't finished, and it really didn't

look very nice."

ProScena Studio - Civil

Support Team (CST) simulation

"The ADL commissioned us to basically redo it in a component-based

simulation," he says, "and in a very short time frame. So we did it in

about six weeks. And now we have to do two more in six weeks to demonstrate how

we can amortize the costs again and again in a variety of different

circumstances."

The simulation is designed to train emergency rescue workers in responding to

a hazardous materials incident. The scene is the Orlando airport, which you see

in a first-person view just like in a video game, exploring within a 3D model of

the airport and viewing your team members walking along with you. You start

outside the building across the street from the terminal, where you join the

other members of your team, and also meet the virtual instructor character who

briefs you on the mission. The application also provides an accompanying set of

web pages to define the concepts used in the mission.

"The instructor guides you through a sampling mission to identify a

puddle of chemicals," says Lane, "all the while maintaining the

situational integrity of the site to follow chain of custody, and following

other procedures to make sure that, as a crime site, it doesn't get

contaminated."

The simulation also can be run across a network so that the three principal

members of the team, the chief, the sampler, and the assistant, can interact.

The team members communicate using voice, just as in the real world, and not

with typing or other video game shortcuts.

This emphasis on verisimilitude, however, can be something of a shock to

video game fans. Walking in real life is a very tedious process, compared to

running, jumping and flying in a video game fantasy. "It's slow, just like

it is in real life," says Vincent Thomasino, chief technical officer at

SoVoz. "The National Guard was pretty adamant about the realism. So when

you walk, you lumber along."

"These guys are all in hazmat suits," says Lane. "They have an

hour of air, and it takes some 15 minutes to get in and 15 minutes to get out.

So they have to be aware of the time, and what they can do in the time

allotted."

But for demos, and even for some training, it can make sense to cheat a bit.

"If you're doing a drill you can fast-forward," says Lane. "You

want to structure it in such a way that people get the repetition in. But when

they go into the actual exercise part, then it's done in a way that maps to

reality."

"The interesting thing about serious games," says Thomasino,

"is that a lot of the time, the things that we take for granted in games --

the ability to fast-forward, the trade-offs between fun and realism -- all skew

the other way, towards realism and not fun. Which can make the simulations

themselves kind of boring," at least if you're evaluating them solely as

entertainment.

How promising are game-based simulations, when the development costs for top

games have gone Hollywood? High-end games have budgets of $5 to $20 million,

Lane estimates, and involve teams from 50 to 200 people working from 18 months

to two years. "And even for a serous game project, something to use in

training or education, you're talking $50,000 to $200,000 and three to four

people working on it."

As a result, says Lane, "people are locked out of the market because of

the price point, so there is a need in the market for toolsets that can help

drive the price down."

SoVoz actually uses a commercial game engine for its 3D graphics, NDL

Gamebryo (www.ndl.com). "We had a base

of 3D technology," says Lane, "because of the speed at which that

technology is advancing we decided that it did not make sense to maintain our

own engine. This allows us to leverage the NDL engine, not only in terms of

performance, but also for cross-platform capabilities, since it also runs on

game consoles. So now we have a high-level scenario authoring system that uses

commercial game technology."

The other issue in creating simulation-based applications is the need to

depend on programmers to translate the designer's vision into the final software

implementation.

"In the past," says Thomasino, "the game designer, or subject

matter expert, had been typically locked out of the process because they had no

means by which they could interact with the application and contribute to the

end design."

With traditional methods, says Lane, "you would have to hire a company,

and they would program the whole thing for you, and then deliver it to you. The

timeframe is long, and your ability to customize it is limited."

SoVoz takes a different approach. "The intent here is to build a

toolset," Lane says, "that can draw on a library of objects, actors,

and behaviors, so you can very quickly prototype a scene or scenario."

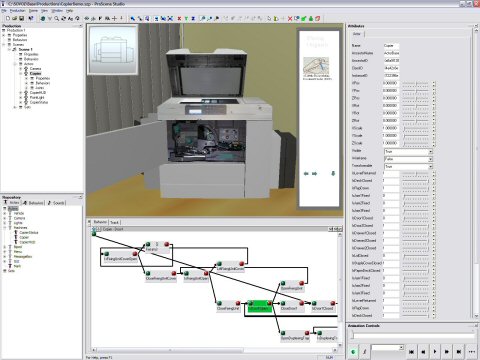

Copier repair simulation

In the SoVoz tool, says Thomasino, "the user interface acts as a

rallying point between the three principal players in the development process:

the artist, the programmer, and the game designer. This serves as the

centerpiece of the development effort. It allows each of these individuals to

work in parallel without having all the dependencies of typical

development."

"The whole idea is to simplify the development of games and

simulations," he says. "We want to bring the price down to the point

where people who want to build serious games, but who have smaller budgets and

smaller time frames, can get involved in building a simulation without having to

hire a lot of expensive experts."

SoVoz is interested in marketing both products and services, so it is

targeting a price range of "somewhere between $5,000 and $25,000,"

says Lane, "depending on how we work with the end user."

Says Thomasino, "We want to get it to the point that people are pointing

and clicking, rather than writing textual code."

SoVoz has developed an infantry simulation for a hostage rescue scenario.

Again, the inspiration was a previous Army project, which had been implemented

in VRML (a now-outdated Web-based 3D environment). "It was severely

limited," says Lane, "and they wanted to see if they could create a

set of tools to author the content and have it run the way they expect."

After all, what are the alternatives for training EMT workers or soldiers in

these kinds of large-scale missions? You only can go so far with book and

classroom learning, and running a full-scale live exercise is so daunting that

it can only be done occasionally. As a result, real-life exercises and

large-scale mock incidents cannot provide individualized training, much less

repetition to build skills.

"There really is a need for something intermediate," says Lane,

"a simulation that will allow people to apply what they have learned in the

classroom, especially if you are dealing with hazardous materials or

explosions."

But while this hostage rescue simulation may look like a typical shoot-em-up

video game, with soldiers running among buildings and shooting at each other,

that's not the point of the exercise.

Hostage rescue simulation

Hostage rescue simulation

"The intent is not to teach how to be an infantryman," says

Thomasino. "Games are not intended to provide that level of training.

Rather it is to teach team coordination skills, specifically for a team leader

to learn how to direct your soldiers into battle."

The simulation is designed in the SoVoz authoring system using a directorial

metaphor, in which the total simulation is called a production, which is then

composed of many scenes, each of which is an independent lesson or sequence. You

can populate the scene by picking from a repository of pre-built components,

including static elements to build the set, such as the Orlando airport

terminal, and active elements that are the actors in the scene, such as enemy

soldiers.

The sets and actors are fully 3D models, created in industry-standard

authoring tools such as Discreet / Autodesk 3D Studio Max (www.discreet.com)

and Alias Maya (www.alias.com).

Objects can be designed at the level of detail required for the simulation, so

the people are fully articulated and vehicles have wheels that can be steered.

Even better, the object designer can also associate basic animated behaviors

with the models, so the people can walk, and crouch, and step forward and lift a

gun to shoot.

Then the game designer can build hierarchies of higher-level behaviors, so a

vehicle can be accelerated and steered, or even follow a road, or a human can

walk to a destination point, or even follow a moving target as they walk. The

authoring environment includes constraints from the physical world, so an actor

cannot walk through walls, and a vehicle can collide with an object and knock it

over.

In the hostage rescue simulation, the team members have even more

sophisticated behaviors. "They're smart enough that they can operate on

their own," says Lane, "but I can also give them individual commands.

They know about the objective, and they have a series of orders that they're

following."

Nevertheless, this simulation is about team leadership. "I can

participate in the shooting," says Thomasino, "but the objective is to

rescue the hostage, according to the procedures set forth in the mission

briefing. My team is arrayed around me, but they'll be killed if I don't support

them properly. If I utilize the resources correctly, and I deploy them properly,

I can maximize the amount of force that's brought to bear on the target."

While the simulation can be published as a stand-alone application for

training, it also can be run directly within the soVoz authoring environment, so

the trainer or designer has the ability to change the configuration. And since

the system manages behaviors separately from actors, you can import new objects,

like a different vehicle or soldier, and simply map the logic from pre-existing

high-level behaviors onto the new model.

This focus on intelligent actors grew out of Lane's work with his previous

companies, and from his original focus on engineering and robotics. He earned

his undergraduate degree in mechanical and aerospace engineering from Cornell in

1980, followed by a M.S. in systems engineering from UCLA. He then came to

Princeton University, where he received a M.A. and Ph.D. in mechanical and

aerospace engineering. After graduating from Princeton in 1988, he co-founded Robicon

Systems Inc. with Dave Handelman to develop technology to help robots learn,

using artificial intelligence (AI) based upon biological principles.

However, intelligent robots do not need to be physical objects, and that work

evolved into smart agents that had interesting potential applications for

entertainment and the growing Internet. In 1993 Lane and Handelman co-founded Katrix,

Inc. to commercialize the robotics and AI technology developed at Robicon

for use in the interactive entertainment and computer animation markets.

"We intended to commercialize this stuff in the entertainment area,"

says Lane. "We were developing the technology, and because we needed

production capability we hooked up with Christopher Gentile and formed Millennium

RUSH." Their interactive character animation technology led to game

projects with companies including Hasbro, Disney, Intel, Microsoft, and

AT&T.

After Katrix, the team split up to pursue different interests. Handelman

founded American Android Corp. in Princeton to apply and extend the

technology for humanoid robotics research and development (www.americanandroid.com).

Gentile founded MC Squared Incorporated in Pennington, N.J. to develop

and produce technologies and content for the entertainment industry (www.mcsqd.com).

And Lane hooked up with Thomasino to form soVoz in 1999 to commercialize

behavioral animation technology for web-based intelligent agents.

Thomasino graduated from Johns Hopkins in 1996 with bachelor's degrees in

computer science and political science. He worked at Bell Atlantic and then at

Eastman Kodak, where he designed and developed a web-based workflow and imaging

system. "I was getting out of Kodak," says Thomasino, "and was

looking to do something different and interesting. Steve was looking to do

characters on the Web, and I had the background to do the infrastructure. And

this is vastly more exciting."

"After Katrix, I was really interested in characters on the

Internet," says Lane. "The idea was intelligent agents -- sales agents

-- characters that could facilitate selling merchandise. So I raised some angel

funding and we set up shop in Manhattan, Silicon Alley, and started to build out

this system. We were working with an electronics website, and we had stuff up

and running. You could view items on the site, and characters would come out and

negotiate pricing and try to upsell you."

But after the dot-com debacle, "the bottom fell out of the market and we

had to refocus," he says. "We couldn't raise the second round of

financing. We went into hibernation, and really started again in 2002."

Oh, and the company name? "Since we were developing intelligent agents

for E-commerce applications in the dotcom days," says Lane, "the name

soVoz was derived from the Latin words socius and ovo to roughly mean 'agent

source.' As we moved into the visualization and simulation area, we needed a

unique name that could be branded however we liked, so we decided to stick with

soVoz."

To fund the further development of the technology, soVoz won Small

Business Innovation Research (SBIR) contracts with the Office of the

Secretary of Defense (OSD), the U.S. Army, and the Office of Naval Research (www.acq.osd.mil/sadbu/sbir).

This program sets aside a billion dollars a year in early-stage R&D funding

for small technology companies (fewer than 500 employees), for projects that

serve a DoD need and have commercial applications. (One success story: an

accelerometer now used in most DoD missile systems, including the Patriot, which

also has been adopted by Ford and Chrysler to trigger airbags.)

"It's a three-phase program," says Lane. "Phase 1 is six

months, usually $100,000, and it's more of a feasibility study. The government

issues solicitations for topics they need and you respond with a 25 page

proposal, and if you win, it's a feasibility study. If they like what they see,

in phase 2 they ask you to submit a proposal to build a prototype. That can be

up to $750,000 for two years. And that's what we've been doing here. Then phase

3 is usually a commercialization effort. If you are building something the

government really wants, in phase 3 they will issue a procurement contract, or

it could be to raise venture capital. We also got a phase 2 plus contract, which

is additional R&D to enhance the product. It requires some matching funds,

in our case from ADL (the Advanced Distributed Learning initiative), our

customer."

With this and other funding, soVoz maintains a staff of five as it enhances

its technology and develops prototype simulations to demonstrate its

capabilities. In his spare time, Lane is an adjunct professor of computer

science department at Penn, teaching courses in computer graphics and animation.

Serious games promise great potential for "learning by doing" in a

wide range of applications, ranging across emergency response team training;

equipment assembly and repair; 3D product demonstrations and visualizations;

tactical operations training and mission rehearsal; and corporate sales and

customer service training.

But is there a market for what soVoz is doing, and how can they make a

business from it?

Video gaming is a tough business. "Having been in the game

business," says Lane, "we know how it is so crazy, especially

schedules. The thing that is appealing about the serious games space is that

it's unlike the game area, where the cool factor is what sells the games, and

you're never really sure until you ship the title if it is going to be

successful or not. In the serious games space, you can motivate what you're

doing based on time and money. It's a more stable business."

The other advantage, says Thomasino, is that "unlike with a game where

you have to create the original intellectual property, which is a monumental

intellectual effort to construct characters and the world, here most people

understand the application intuitively and have already documented it

thoroughly. The business model makes a lot more sense because there's no

guesswork. We already know there's demand. You just have to get the simulation

right and at the right price point."

So is this a tools business?

"Originally, when we started the project back in 2001 - 2002," says

Lane, "we were thinking shrink-wrapped products in three different

versions: one for personal, and then more a professional version and an

enterprise version. But as things have evolved, and as we talk to people, about

how they envision using it, it's clear that a service component is necessary.

The enterprise version is reasonable, where someone buys the tool and all its

capability, and has people on staff to do what they need to do."

But for smaller shops, says Thomasino, "we keep encountering companies

who want to do this kind of thing, but they don't have the capabilities. It's

completely alien to them, so to build up a production staff that would be

capable of doing this is outside the scope of what they are doing. They would

rather hire us, so we use the tool as a competitive advantage."

However, says Lane, "the landscape is littered with lots of companies

that tried to build tools, because they're very technology intensive for going

with a stand-alone product, and over time, the price points are coming down.

When products like Alias first came out, they were selling them for $40,000 a

pop, and now they are $5,000. We don't want to fall into that trap."

So the answer is to provide both products and services, and to grow both the

underlying technology and the value-added components for specific markets.

"We're trying to focus on various niche markets," says Lane, "so

the question is what's the right business model. There is a business model for

gaming, game publishing, so we are taking the approach now that we are working

with the training companies, who are our customers, and we are giving them value

added content for the training that they provide."

But another issue is distrust of simulation-based training, as not only new

and different, but because of its association with video games. "There are

a lot of people interested in it," says Lane, "but the problem is a

lot of people in corporations who were in charge of the training budget are from

a different generation. So the thought of spending money on something game-like

is a foreign concept. This will change over the next few years as the first

Nintendo generation -- people in their early 40s who grew up playing games --

starts to move up."

"This is still very much an R&D effort," says Lane. "We

are not out there with the sales staff trying to close the deals; we are working

with the government, and other companies that are servicing the homeland

security sector."

"What we see in terms of serious games is the need for this kind of a

tool set, and we want to be there and ready to go as that market unfolds."

soVoz, Inc.

www.sovoz.com

American Android Corp.

www.americanandroid.com

MC Squared Incorporated

www.mcsqd.com

Game Developers Conference (GDC)

www.gdconf.com

Serious Games Summit at GDC

www.seriousgamessummit.com

Serious Games Initiative

www.seriousgames.org

Social Impact Games

www.socialimpactgames.com

Advanced Distributed Learning (ADL) Initiative

www.adlnet.org

The Interservice/Industry Training, Simulation and Education Conference (I/ITSEC)

www.iitsec.org

Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) Program

www.acq.osd.mil/sadbu/sbir

Discreet / Autodesk - 3D Studio Max - 3D animation, modeling, and rendering

www.discreet.com

Alias - Maya - 3D modeling, animation, effects, and rendering

www.alias.com

NDL (Numerical Design Limited) - Gamebryo - 3D graphics engine

www.ndl.com

|