Manifest Technology Blog

-- Site:

| Articles

| Galleries

| Resources

| DVI Tech

| About

| Site Map

|

Articles:

| PC Video

| Web Media

| DVD & CD

| Portable Media

| Digital Imaging

| Wireless Media

| Home Media

| Tech & Society

|

PC Video: |

PC Video Articles |

Video Software Gallery |

Video Editing Resources |

Next-Generation Video:

MPEG-4 and Streaming Media (4/2003)

by Douglas Dixon

MPEG Standards

The MPEG-4 Industry

Apple QuickTime

RealNetworks

Microsoft Windows Media

Better Quality

The Interactive Future

References

Streaming media is no longer just postage-stamp videos stuttering over a

dial-up connection. The past few years have seen the development of the MPEG-4

standard and its adoption into architectures like Apple QuickTime, and

technology improvements in compression, servers, and players in systems such as

RealNetworks RealMedia and Microsoft Windows Media. Each of these approaches has

grown far beyond just video and audio compression, to end-to-end systems for

creation, hosting, delivery, and playback of a broad range of multimedia data.

With continued rapid innovation and competition, streaming media has expanded

from video windows to full-resolution movies, from networks to wireless devices,

and from computers to portable audio devices and DVD players. For content

creators, they offer the potential of distribution paths from tiny mobile phones

to digital cinema. And, with digital rights management, they offer a market for

renting and selling videos over the Internet.

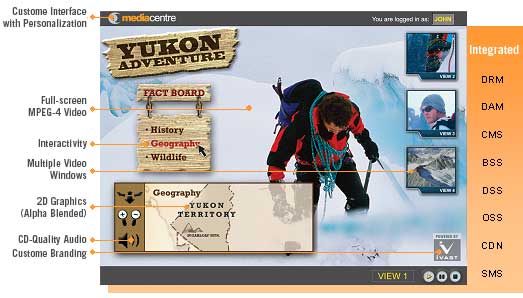

And this is still just the beginning, as architectures like MPEG-4 extend

beyond just video playback: by separating video content into objects and layers

they promise a much more customizable and interactive experience.

Yet all this activity and excitement also makes the streaming market

confusing and frustrating, with rapid change and multiple competing formats to

understand and choose between, even before trying to deal with the huge

variations in the quality of the streaming experience at different bandwidths.

The Moving Picture Experts Group (MPEG, www.chiariglione.org/mpeg/standards.htm)

has developed a series of standards to drive the development of digital media,

from CD to DVD to streaming. The MPEG compression standards provide common

formats for storing, sharing, and playing video and audio. They offer the

ability to "author once, play anywhere," and provide users the

confidence that their assets will remain accessible. Standards also can drive

innovation and choice though competition.

MPEG-1, approved in 1994, was designed for stored media, especially CD-ROM

applications, with quarter-screen, "VHS-quality" video. It supports

data rates around 1.5 Megabits per second, and is also used for the Video CD

format.

MPEG-2, approved in 1994, was designed for digital television, with a data

rate around 4 to 9 Mbits/sec, and scalable to high definition. Its most obvious

success is in the explosive popularity of DVD, and it also is used in digital

set-top boxes and cable and satellite TV.

MPEG-4, approved in 1998, provides scalable quality, not only to high

resolution, but also extended to lower resolution and lower bandwidth

applications. It also supports scalable delivery, with error resilience features

for delivery across difficult channels including the Internet, satellite, and

wireless.

The MPEG-4 specification also includes a new audio format, AAC (Advanced

Audio Coding), developed by many of the companies involved with the creation of

MP3 and Dolby AC3.

MPEG-4 also is a system, a standard for multimedia applications: not just a

stream of video and audio, but a collection of media objects, natural and

synthetic, that can be combined, synchronized, and delivered to a player.

(Just so you know, there was no MPEG-3 standard, and "MP3" is not

MPEG-3, but instead is a shorthand for MPEG-1, Layer 3 audio compression. The

MPEG committee is also working on MPEG-7 and MPEG-21 standards for multimedia

interfaces and frameworks.)

MPEG-4 is supported by a variety of industry groups in different markets.

The MPEG-4 Industry Forum (M4IF, www.m4if.org)

has over 100 members, working "to further the adoption of the MPEG-4

Standard, by establishing MPEG-4 as an accepted and widely used standard among

application developers, service providers, content creators and end users."

Its web site has a wealth of information on MPEG-4, links to external resources

and MPEG-4 products, and is updated at least daily with MPEG-4 news.

MPEG-4 has seen strong adoption in the wireless industry, through groups such

as the Third Generation Partnership Project (3GPP, www.3gpp.org),

which brings together a number of telecommunications standards bodies to produce

global standards for third generation mobile systems.

Within the streaming industry, the Internet Streaming Media Alliance

(ISMA, www.isma.tv)

was founded by Apple, Cisco, IBM, Kasenna, Philips and Sun "to accelerate

the adoption of open standards for streaming rich media - video, audio, and

associated data - over the Internet." Its members come from all points of

the streaming workflow, including content (AOL Time Warner) and delivery (Envivio,

Inktomi, iVast), computer (SGI), consumer (Hitachi, Panasonic, Sharp, Sony), and

chips (Analog Devices, National Semiconductor). ISMA adopts and promotes

existing standards to define end-to-end system specifications for cross-platform

and multi-vendor interoperability.

Unfortunately, the deployment of MPEG-4 has been delayed by disputes about

the licensing terms. The MPEG LA licensing authority (www.mpegla.com)

represents companies holding patents for technology used in the standard. The

provisional licensing terms proposed in early 2002 not only included separate

fees for encoders, decoders, and encoded data, but also imposed per-minute

streaming fees. After significant objections from the streaming community, the

terms were revised in July 2002 to provide more flexible terms and to apply only

to commercial products and services.

Apple has been diligently developing QuickTime since 1991 as a cross-platform

architecture for creating, playing, and streaming digital media (www.apple.com/quicktime).

QuickTime is a core technology on the Macintosh platform, and is also available

as a free download for Windows, and is installed with the many applications

built on its platform.

QuickTime has an open architecture that supports over a hundred digital media

formats. For example, QuickTime added support for MPEG-1, MIDI, and QuickTime VR

panoramas in the mid-1990's, and became a popular format for cross-platform

applications with media content on CD. In 1999, QuickTime 4 included support for

DV, MP3, Flash, animation, and Web streaming protocols. QuickTime 5 then became

especially popular as a cross-platform format for posting web videos such as

movie trailers and music videos.

The big news in QuickTime 6, introduced in July 2002, is support for MPEG-4.

QuickTime 6 supports the MPEG-4 file format, MPEG-4 video, and AAC audio. With

server support, it also added Instant-On playback (without waiting for

buffering) and includes Skip Protection to prevent transient interruptions in

streaming.

The QuickTime 6 product suite now includes the free QuickTime Player, the

QuickTime Pro upgrade for content editing (including MPEG-4), and an additional

plug-in for MPEG-2 playback (but not creation). Apple also has moved its servers

to free open source products, with the QuickTime Streaming Server 4 for Mac OS X

(with no streaming license fee), the open-source cross-platform Darwin Streaming

Server, and the QuickTime Broadcaster for live broadcasts.

Apple is positioning QuickTime as the architecture and platform at the center

of digital media, as the "industry-leading, standards-based software for

developing, producing and delivering high-quality audio and video over IP,

wireless and broadband networks." Since Apple has paid the MPEG-4 licensing

fees for the QuickTime architecture, it provides an attractive end-to-end

streaming solution for both users and digital media tool developers.

Apple has been active in driving the MPEG-4 standard, though ISMA and other

venues, and was very visible in delaying the release of QuickTime 6 in order to

force the issue of reasonable licensing fees for streaming. Apple has seen

strong response and interest in QuickTime 6 and MPEG-4, with over 25 million

downloads in the 100 days after it was released.

Apple sees QuickTime 6 as a platform for digital multimedia producers that

enables the distribution of content to any MPEG-4-compliant device. By

supporting the MPEG-4 file format and its "author once, play

everywhere" capabilities, QuickTime 6 "delivers scalable, high-quality

video and audio for distribution to networks ranging from narrowband (cell phone

networks and modem connections) all the way to broadband and broadcast."

While QuickTime's legacy is in playing video files as a media platform,

RealNetworks (www.realnetworks.com)

has always been focused on streaming media. From the first RealPlayer for

streaming audio in 1995, Real has driven the development of its RealMedia audio

and video compression formats, and its server and player products for delivering

and viewing media content. RealVideo 9, introduced in April 2002, provides 30%

bandwidth savings over RealVideo 8, and the Real tools now also support MPEG-4.

RealNetworks has become the ubiquitous streaming format on the Internet (www.real.com).

As of mid-2002, more than 2500 live radio stations broadcast over the Internet

using RealAudio, there are more than 285 million registered uses of the

RealPlayer, the RealPlayer is installed on over 90% of U.S. home PCs, and over

85% of Web pages that contain streaming media use RealNetworks formats.

However, while Microsoft and Apple have preloaded support on their native

Windows and Mac OS platforms, and can give away their media architectures and

tools for free in order to drive adoption of their larger platforms,

RealNetworks needs to generate profits from streaming technology. But, at the

same time, Real also needs to provide an easy entry into its products, and to

drive the use of its formats. As a result, it walks a difficult line, offering

free entry-level tools, players, content creation, and servers, and then

charging for upgrades to full functionality.

More recently, Real has moved into the content delivery business, offering

audio, video, and even games. GamePass offers a new full version game for $6.95

a month with the RealArcade game service. RadioPass offers 50 ad-free radio

stations for $5.95 a month, and MusicPass also offers up to 100 music downloads

for $9.95 a month. The RealOne SuperPass subscription service (www.realone.com)

provides access to premium programming for $9.95 a month, and has more than

750,000 subscribers. Its channels include news (ABC, CNN, Wall Street Journal),

sports (MLB, NBA, NASCAR, Fox, CNN/SI), E! and iFilm videos.

Meanwhile, Real has continued to upgrade its own RealVideo and RealAudio

compression formats. RealVideo 9 and RealAudio Surround support half-screen

video at dial-up rates, VHS quality over broadband starting at 160 Kbps,

near-DVD quality video and surround sound audio at 500 Kbps, and up to HDTV

formats and resolutions. At these rates, two full-length movies can fit on a CD,

and up to fifteen movies on a DVD.

Even with its own formats, Real is positioning its players and servers as

universal platforms that support all other formats. The free RealOne Player

version 2 plays streaming media, DVD, and MP3, and also burns CDs. The RealOne

Player Plus upgrade ($29.95) adds universal playback of over 50 additional media

types, including Windows Media and QuickTime MPEG-4.

Real's Helix Universal Server, released in July 2002, streams all major media

types, including Real, QuickTime, MPEG-2, MPEG-4, and Windows Media. Real offers

the source code of the Helix DNA platform under commercial and open source

licenses through the Helix Community (www.helixcommunity.org).

The Helix server is available on Windows, Unix, and Linux. Real also is working

to deploy its formats on non-PC and embedded devices such as Palm OS and with

partners including Hitachi, NEC, Nokia, and Philips.

While Apple has moved QuickTime wholeheartedly behind MPEG-4, and Real plays

both sides of the street as a universal platform that also maintains its strong

emphasis on the RealMedia formats, Microsoft continues its major investment

focused on the Windows Media format and architecture (www.microsoft.com/windowsmedia).

While the Windows Media format originally evolved from MPEG-4, Microsoft is

positioning Windows Media not just as better compression beyond standards such

as MPEG-4 and MP3, but as a complete end-to-end digital media platform, with

content creation tools, servers, clients, and application programming

interfaces.

Windows Media 9, introduced in beta in September 2002, is a major end-to-end

upgrade of the entire system. Video compression has improved 15 to 50 percent

over Windows Media 8. It includes enhancements for dial-up rates with video

Frame Smoothing and mixed-mode voice and music audio. It also extends upward to

digital cinema, with 1280 x 720 and 1980 x 1080 (hardware-assisted) progressive

video and 5.1 surround-sound audio.

Windows Media Player 9 supports multiple bit rates and languages in a single

stream, and provides variable-speed playback without changing the audio pitch.

It also delivers Fast Streaming instant-on/always-on streaming for broadband.

The Windows Media 9 servers provide content providers with features including ad

insertion and server-side playlists for organizing content delivery. Microsoft

also has enhanced its Digital Rights Management (DRM) technology to provide a

complete system for content sales and rental.

Microsoft is deploying the Windows Media format beyond the desktop, to

PocketPC handhelds and to a wide array of consumer electronics devices. Windows

Media Audio already has been built in to portable audio players, CD players, and

car stereos (as MP3 has been). And now Windows Media Video is being built in to

DVD players as an alternate format to MPEG-2, and can squeeze longer movies onto

a disc. Microsoft predicts that by the end of 2002 there will be approximately

27 million consumer devices supporting Windows Media formats.

Even better, all these elements are free, bundled with the latest Microsoft

server and operating systems releases, or available for download. While the new

Windows Media 9 formats are backward compatible with Media Player 7.1 and older

consumer devices, the advanced capabilities do require Windows .NET Server and

Windows XP.

While MPEG-4 is gathering momentum and support, especially for streaming and

wireless, RealNetworks and Microsoft argue that it is by now an old standard,

while their formats and technology have continued to rapidly evolve and improve.

These formats are being positioned as defacto standards, as they are embedded in

chips and built into consumer electronics devices.

Microsoft describes Windows Media 9 as three times better than MPEG-2 (for

example, DVD quality at 2 vs. 6 Mbps), and twice as good as MPEG-4. In comparing

current implementations, Real and Microsoft's focus on compression improvements

has resulted in better quality than the basic MPEG-4 profile provided in

QuickTime 6.

While the benefits of a common standard such as MPEG-4 may well be worth

giving up some compression performance, the question now is whether the combined

efforts of the wide range of companies involved with MPEG-4 also can advance the

technology and implementations to take full advantage of the format.

The standards community also is not standing still. MPEG has partnered with

the International Telecommunications Union standards group to form the Joint

Video Team (JVT) to define enhancements to MPEG-4. This new version, Advanced

Video Compression (AVC), is targeted to provide 50 percent better compression

and improve support for mobile networks and the Internet.

MPEG-4 is much more than a compression format. It is a container for a

variety of media data types and associated information, based on Apple's

QuickTime file format. It supports both natural and synthetic objects; not just

recorded audio and video, but also text and sprites, synthesized music and

speech, 2-D and 3-D graphics, and even face and body animation.

MPEG-4 then provides a mechanism to combine these media objects into

audiovisual scenes, and then multiplex and synchronize the data to package it

for delivery over different types of channels. In MPEG-4, the content is defined

in terms of the scene and its independent objects, and not all smushed into

pixels in a frame of video. As a result, streaming media experiences can be

choreographed and animated as with computer graphics.

Similarly, the viewer can go beyond passive viewing to interact with the

scene and the objects. This provides a much more sophisticated experience than

is possible with just video, and transmitting individual objects and behaviors

that can be modified over time also provides large savings in bandwidth,

especially the interaction can be managed on the client side.

So, what does this all mean for the future? In the short term, while it is

clear that the market will continue to be confused and fragmented by multiple

competing formats, the resulting competition also promises continued advances in

compression performance and quality. In the longer term, object-based

compression promises a revolution in how we experience digital media, with much

more flexible and interactive experiences for entertainment and education.

Whether at the desktop or on a handheld device, life will continue to be

interesting.

Moving Picture Experts Group (MPEG)

mpeg.telecomitalialab.com ->

www.chiariglione.org/mpeg/standards.htm

MPEG LA licensing authority

www.mpegla.com

MPEG-4 Industry Forum (M4IF)

www.m4if.org

Internet Streaming Media Alliance (ISMA)

www.isma.tv

Third Generation Partnership Project (3GPP)

www.3gpp.org

Apple QuickTime

www.apple.com/quicktime

RealNetworks

www.realnetworks.com

www.real.com

www.realone.com

www.helixcommunity.org

Microsoft Windows Media

www.microsoft.com/windowsmedia

|